7.3 Pure Tones, Consonance and Dissonance

We briefly discussed the perception of consonance and dissonance of pure tones in Section 5.5. We stated that beat frequencies in the range of 10 – 50 Hz are annoying to the ear. We can now explain this in a bit more detail based on the structure of the ear that we developed in the last two sections.

Two pure tones played together:

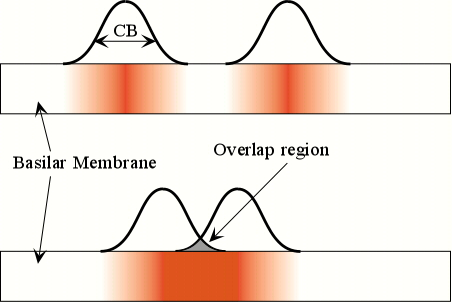

Loudness. The first consequence of the Critical Bandwidth is on how the loudness of two tones is perceived. If two tones are within the critical bandwidth, the combination does not sound as loud as if they are separated by more than the CB:

If the two tones are quite separate in frequency, as much of the Basilar Membrane is activated as possible. However, if the CB of the tones overlap, a smaller part of the membrane is activated, and the two tones do not sound as loud. If the neurons are already firing in response to one tone, it does not help to have the other tone also trying to make them fire.

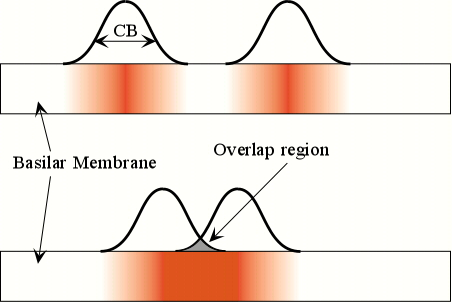

Roughness. If tones are overlapping, there is a region on the Basilar Membrane where the neurons are trying to respond to both tones. The problem is that the neurons don’t know which frequency to follow. The neurons end up jumping back and forth between the two frequencies. This gives rises to a rough or unpleasant sensation. It also makes it hard to focus ones attention on just one of the two tones.

Perception of two pure tones f1 and f2.

We are now in a position to analyze what two pure tones will sound like based on the difference of the two frequencies. If:

|

|f1 – f2| |

< 10 Hz. |

You hear a single pitch equal to the average frequency ½ (f1 + f2). However, you will also hear beats. |

|

|

> 15 Hz |

Still hear one tone, but brain can no longer follow the beat frequency. The Critical Bandwidths are overlapping so the neurons fire irregularly creating dissonance. A difference frequency of 30-40 Hz is the worst in terms of dissonance or roughness. |

|

|

> half step |

E.g. 60 Hz at 1000 Hz. You can begin to hear two separate tones, but the C.B.’s are still overlapping, so the tones are dissonant. |

|

|

> C.B. |

E.g. 190 Hz at 1000 Hz. Now, you hear two distinct tones and they sound consonant. You can also begin to hear a difference tone. |

Notice how the frequencies of the notes will affect the perception. The first distinctions, 10 Hz, 15, Hz and 30-40 Hz are absolute frequencies, and are independent of the frequencies of the individual notes. The last to conditions (> half step and > C.B.) are defined relative to the frequencies of the two notes. Thus, these conditions will apply differently for different ranges of frequencies.

For example, consider a Perfect Fifth between C = 64 Hz and G = 96 Hz. Usually, the Perfect Fifth is considered to be a consonant interval, even with complex tones. However, the difference between these two frequencies is 32 Hz. This is in the range of dissonance. Thus, normally consonant intervals, when played at very low frequencies will sound dissonant. For this reason, composers rarely use a simple Perfect Fifth in the low range of a piano. Rather, they will use the interval of an Octave and a Perfect Fifth. Now, the notes would be C = 64 Hz, and G = 192 Hz. The difference frequency is 128 Hz, well within the range of consonance.

Difference tones:

Once the difference tone exceeds the lowest frequency that you can easily hear, the brain starts to interpret the beat frequency as a new note. For example, if one plays an A = 220 Hz and an E = 330 Hz, the difference tone is at 110 Hz, and it will sound like another note is being played an Octave below the A.