.

.6.4 Sonic Booms and Shock Waves

The basic formulas for the Doppler shift are given in the previous section. However, there are some consequences and uses of the formulas that are not so apparent. We will discuss some of these in this section.

Sonic booms:

Let’s consider the situation where the source is moving towards the observer. The formula for the Doppler shifted frequency is:

.

.

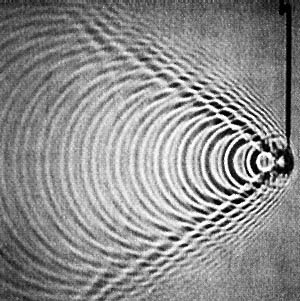

If Vs = 0, which means the source is not moving, the formula gives f’ = f. In other words, the frequency stays the same and there is no Doppler shift. If the source starts moving, the denominator will get smaller, making the ratio bigger and the Doppler shifted frequency, f’, will increase. What happens as the source velocity gets bigger and bigger? The difference Vwave – Vs gets smaller and smaller and f’ gets higher and higher. Now, at some point, the source velocity will exceed the wave velocity. Right at this point, f’ becomes infinite! To get an idea of what this means, let’s look at a picture of the waves when Vs = Vwave:

Because the source is now traveling at the same velocity as the waves, the waves never get ahead of the source, and the waves all pile up at one point. The distance between the waves goes to zero and so the frequency becomes very high. More importantly, all of the energy gets concentrated into a very small distance – this is called a shock wave. In this case, the observer does not hear the approaching source at all until the shock wave hits with all of the energy in the wave. For sound waves, this can cause a very loud noise, called a sonic boom. Any time a source exceeds the speed of the wave, a shock wave will be formed.

If the source is traveling faster than the waves, the waves never catch up to the source, and a different sort of pattern is formed:

The shape of the shock wave is called a Mach cone and the opening angle of the cone is given by:

Sin(q) = Vsound/Vsource

Each kind of wave has it own example of shock waves and Mach cones.

Water waves:

The easiest waves to visualize are water waves. In this case, you just need to drive a boat faster than the speed of water waves, which is not hard to do:

The Mach cone is even better in a controlled experiment:

Sound waves:

Sound waves are harder to visualize, but they are easy to hear. If a jet exceeds the speed of sound, it produces a loud sonic boom, which can even rattle or break windows. Jets are no longer allowed to fly faster than the speed of sound, over cities, at least.

However, with some sophisticated photography, the Mach cone in air can be seen:

A few years ago, a car actually went fast enough to break the sound barrier. In this case, the shock wave kicked up dust as it went past. In the following picture, you can see where the shock wave is in relationship to the car:

Light waves:

Can you produce a shock wave of light? You might answer no, because to create a shock wave, something must travel faster than the wave. Since nothing can travel faster than the speed of light this could never happen. However, this is not quite true. In a transparent material, like glass, light does slow down by a factor called the "index of refraction". The index of refraction of most types of glass is about 1.5. So, inside of a piece of glass, only travels about 67% of its normal speed. This means that a very fast particle can actually exceed the speed of light in a material. If you accelerate electrons to a very high velocity and fire them into a piece of glass or plastic, they will produce a shock wave of light that you can see. This light is called "Cherenkov radiation".

The following picture shows a nuclear reactor. In the reactor, uranium atoms give off energetic neutrons. These neutrons collide with electrons and give them very high velocities. The entire reactor is underwater to keep it cool. In the water, the speed of light is reduced, just like in glass. The electrons then produce Cherenkov radiation, which appears as a bluish glow.

Reference frames and double Doppler shifts

One final issue needs to be discussed with respect to the Doppler effect. We noted above that if the source and the observer were coming towards each other, the frequency of a tone would increase. However, if we look at the formulas for the moving source and moving observer, the amount of the increase will be different depending on whether the source or the observer is moving.

Now, it may seem like a simple matter to determine which is moving, the source or the observer. However, it is not so simple. Say that you are standing by the side of a road, listening for a siren. You would say that you are stationary, and it an ambulance passes by, that is a case of a moving source.

Although you are just standing by the side of the road, you are also standing on the Earth, which is spinning. It is also orbiting the Sun at a very high velocity. Not only that, the Sun is orbiting the center of the galaxy, again, with a high velocity. So, are you moving or stationary? Ultimately, any question relating to whether or not you are moving, must specify with respect to what? If I am standing in the classroom, I am not moving with respect to the desk. However, I am moving with respect to the Sun. The system by which you are judging the motion is called the "frame of reference". If you are sitting in a car traveling at 60 miles/hour and you are holding a coffee cup, you don’t think of the cup as moving, because the obvious frame of reference is your hand. With respect to the ground, the cup is traveling at 60 miles/hour, but that does not affect your ability to drink from the cup.

So, now, an interesting questions arises: when it comes to the Doppler effect and the difference between a moving source and a moving observer, what frame of reference is used to determine which is moving? Actually, there is a very precise answer to this question: since we are talking about waves, there must always be a medium present for the waves to travel in and, so, the medium is the frame of reference for measuring all motion.

For example, if you are standing outside and the air is still, you are not moving with respect to the medium for sound (which is the air). If the wind starts blowing at 20 miles/hour, you are no longer stationary – you are actually moving at 20 miles/hour with respect to the air. If a car is traveling at 20 miles/hour in the same direction that the wind is blowing, the car is actually not moving with respect to the air.

As another example, consider a sailboat tied up at a dock, again with the wind blowing at 20 miles/hour. You feel the wind blowing against you, so you must be moving with respect to the air. Now, if you are sailing downwind, the boat is being carried along at 20 miles/hour by the wind. Under those conditions, the boat feels quite calm – you don’t feel any wind. So, in this case, you are now stationary with respect to the air.

Double Doppler shifts:

Understanding reference frames allows us to calculate a more difficult problem: what is the Doppler shift if both the source and the observer are moving? This would be called a double Doppler shift.

In any problem where both source and observer are moving, the solution involves breaking the problem down into two pieces. First, calculate the Doppler shift for an intermediate observer at rest in the medium. This just requires applying the formula for a moving source, because the intermediate observer is not moving. Once this intermediate frequency is determined, consider the intermediate observer as a source, at rest, sending out the intermediate frequency. This is now a problem of a moving observer, since the (intermediate) source is at rest in the medium. It is a little tricky to work this out, but it just requires two steps instead of one.

Doppler shifts through reflection:

One of the most common applications of Doppler shifts is in determining the speed of a moving object, like a car. In fact, bats use this technique to determine the speed of a bug that it wants to catch.

Let’s say that the air is still and a bat is sitting still on a branch and it hears a bug. The bug will send out a high-pitched tone. This tone bounces of the bug and the bat hears the reflected tone. If the bug is not moving, the reflected tone will have the same frequency as the emitted tone. What happens if the bug is moving? As with the double Doppler shift above, we consider the problem in two parts.

First, find out what frequency the bug will hear. This would be a case of a moving observer, as the bat is sitting still. This is the intermediate frequency.

Second, consider the bug to be the source of the intermediate frequency and calculate what the bat would hear. The second part would be a moving source, as the bug acts as the source of the intermediate frequency while the bat is now the observer and is not moving.

Again, this may seem a bit complex, but this is really one way that bats can determine the speed of a bug that it wants to catch. If fact, the bat does more. The shift in frequency is usually rather small, as bugs do not move too fast. Rather than try to sense the small shift in frequency, the bat focuses on the beat frequency between the sound that it produced and the reflected sound.

For example, let’s say the bat produces a tone at 15,000 Hz and a bug is flying away at 1 m/sec. For the first part, we determine the frequency that the bug will hear. This is a moving observer, and the bug and bat are moving apart, so the frequency will go down. The intermediate frequency will be 15,000(1 – (1 m/sec)/(343 m/sec)) = 14956 Hz. In the second part, this intermediate frequency is shifted because the bug is now the source and is moving. So, the final frequency that the bat hears in reflection will be 14956(343/(343+1)) = 14,913 Hz. So, rather than try to detect that change in frequency, the bat listens for the beat frequency between the original 15,000 Hz and the reflected 14,913 Hz. This beat frequency is 87 Hz and is much easier to detect.

Radar guns used to measure the speed of cars works exactly the same way, but with microwaves. Since cars travel much slower than the speed of light, the total shift in frequency is tiny. However, the beat frequency is something easily detected.

Light and the theory of relativity.

One final note: the Doppler shift of light is a little different than for other waves. Why this is is not well understood, but it has to do with frames of reference. Above, we noted that there is a difference between a moving source and a moving observer and motion has defined relative to the medium. By carefully measuring a Doppler shift under the correct conditions, one can determine ones speed relative to the medium. The medium for light is not well understood, but it appears to be the vacuum, or empty space. However, it was realized that through Doppler shifts you can determine whether you are moving with respect to the medium, and so, scientists got excited because they thought they could learn something about the medium for light, or at least how fast we are moving through it. However, when the experiment was attempted to measure our motion with respect to the medium, it failed. It turns out that there is no difference between a moving source and a moving observer when it comes to the Doppler shift of light.

Albert Einstein eventually figured out why this is, and called the answer to this the "Special Theory of Relatively". For this course, we will use the same equations for the Doppler shift of light as for other waves. However, this is another case where light behaves in a peculiar way.