6.3 The Doppler Effect

So far, we have only considered stationary sources of sound and stationary listeners (or observers). However, if either the source or the observer is moving, things change. This is called the Doppler effect. Like the idea of feedback, covered in the last two sections, the Doppler effect has many important applications. Because the Doppler effect depends on things moving, it can generally be used to determine the motion or speed of an object. Objects of interest may be the speed of a car on the highway, the motion of blood flowing through an artery, the rotation of a galaxy, even the expansion of the Universe. As with many fundamental principles in physics, the range of applications can be truly enormous.

So, what is the Doppler effect? One of the most common examples is that of the pitch of a siren on an ambulance or a fire engine. You may have noticed that as a fast moving siren passes by you, the pitch of the siren abruptly drops in pitch. At first, the siren is coming towards you, when the pitch is higher. After passing you, the siren is going away from you and the pitch is lower. This is a manifestation of the Doppler effect.

There are two different situations for the Doppler effect that we will investigate. The first is where the observer is moving. For example, you are in a moving car and are passing by a stationary siren. In the other case, you are stationary, and the source is moving past you. While the second is perhaps the more common situation, the first is easier to analyze. You also might think that these two situations are the same. As it turns out, they are not and this means that you can also learn about who is moving, the source or the observer. We will return to this question in the next section.

Moving observer:

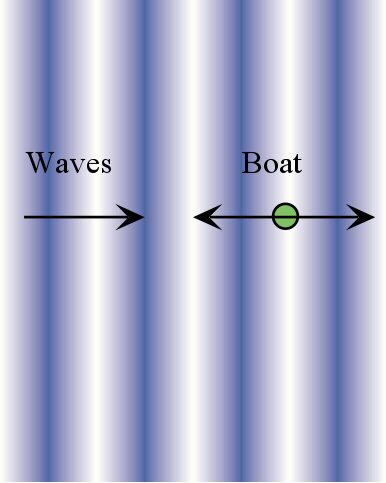

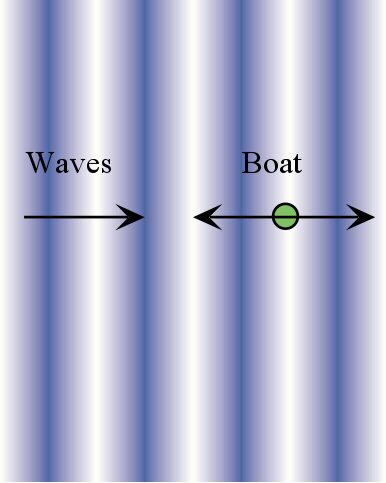

To understand the moving observer, imagine you are in a motorboat on the ocean:

If you are not moving, the boat will bob up and down with a certain frequency determined by the ocean waves coming in. However, imagine that you are moving into the waves fairly quickly. You will find that you bob up and down more rapidly, because you hit the crests of the waves sooner than if you were not moving. So, the frequency of the waves appears to be higher to you than if you were not moving. Notice, the waves themselves have not changed, only your experience of them. Nevertheless, you would way that the frequency has increased. Now imagine that you are returning to shore, and so you are traveling in the same direction as the waves. In this case, the waves may still overtake you, but at a much slower rate you will bob up and down more slowly. In fact, if you travel with exactly the same speed as the waves, you will not bob up and down at all.

The same thing is true for sound waves, or any other waves. If you are moving into a wave, its frequency will appear to you to be higher, while if you are traveling in the same direction as the waves, their frequency will appear to be lower.

The formula for the frequency that the observer will detect depends on the speed of the observer the larger the speed the greater the effect. If we call the speed of the observer, Vo, the frequency the observer detects will be:

Here, f is the original frequency and Vwave is the speed of the wave. However, above, we saw that the Doppler effect depends on the direction that the observer is moving. How does that enter into this formula? If the observer is moving towards the source of the sound the frequency should go up. That is what the formula predicts so far so good. If the observer is moving away from the source, the frequency should go down. How can we make this happen? There are two ways to understand this. We can say that if the observer is moving towards the source, its velocity is positive, or greater than zero, while if it is moving away from the source, its velocity is negative, or less than zero. If you put a negative number for Vo into the formula above, the result will be that the frequency decreases. Alternatively, we can write two formulas, one for the observer moving towards the source, and one for moving away from the source:

Observer moving towards source:

Observer move away from source:

Notice that there is just a change in sign.

What happens if you are moving away from the source, with a speed, Vo equal to the speed of the wave, Vwave? In this case, we would find that f = 0. What does this mean? This is just the case where you are moving along with the waves, and so you dont see the waves going up and down, at all, so there is no frequency to the waves that you are aware of.

Moving source:

The situation where the source is moving is actually a bit more difficult to picture. In the following diagram, the source is the red circle moving to the right. At periodic points in time, it sends off a circular wave. However, once the wave leaves the source, it is no longer affected by the motion of the source the wave just travels on its own. However, when the source sends off the next wave, it will have moved forward a bit. The new wave is a circular wave, just like the previous one, but its center is shifted slightly in the direction that the source is moving. Thus, the wave pattern looks like the following:

Now imagine you are standing on the green dot on the right. You can see that the waves are compressed together. The distance between the crests is the wavelength and so the waves you see will have a shorter wavelength. A shorter wavelength will have a higher frequency. So, if the source is moving towards you, the frequency of the waves will be higher. If you are standing on the left, just the opposite is true: the waves are spread out, so the wavelength is longer, and the frequency is lower. This is a little hard to see on paper, but the Doppler Physlet gives a much better sense of what is going on.

As before, we can write down a formula for the frequency detected by the observer, if we call the velocity of the source Vs:

Source moving towards observer:

Source moving away from observer:

Notice that in both cases, moving observer and moving source, if the source and observer are moving together, the frequency goes up. If they are moving apart, the frequency goes down. However, the amount that the frequency change depends on whether it is the source or the observer that is moving.