4.4 Spectroscopy, Modern Physics and Music of the Spheres

We have now spent quite a bit of time studying waves and some history of physics and music, so it is time to stop for a moment and ask: what have we learned and why is it important? We will take Lab4 as an example of what this is all about. In Lab4 we took a rectangular acoustic cavity and measured its resonant frequencies. While identifying the resonances and matching their frequencies with those predicted from a theory, we obtained a very precise measurement of the speed of sound in the cavity. However, it turns out that the speed of sound depends on the temperature in the cavity. So, in the end, we measured something quite different than what we started out to: the temperature. The acoustic cavity actually makes an O.K. thermometer. This is often the case in physics. If you measure something very carefully and try to construct a theory to explain it, you often find that you learn about something that was seemingly unrelated. This is how science progresses from what is known to what is unknown. This is what also leads to the many useful and important applications of science. Understanding the frequencies of an acoustic cavity led to a method for measuring the temperature. But, there are many more possibilities.

Perhaps we know the temperature from a normal thermometer, but we donít know what kind of gas is in the cavity. However, some other scientist might have made a catalog of the speed of sound in many kinds of gas. By measuring the speed of sound in the cavity through identifying the resonant frequencies, we could determine the kind of gas in the cavity.

We can also proceed in a different direction. In this case, letís assume we know the speed of sound in the cavity, because we know the kind of gas and its temperature. By measuring the resonant frequencies, we can determine the dimensions of the cavity. Of course, we could have just measured the dimensions with a ruler, but measuring frequencies presents an interesting alternative. Why is this so important? There are many situations where a ruler will not work, but we can still measure frequencies:

1) We can measure things that are too small to see. For example, we cannot measure the size of atoms and molecules with a ruler. We cannot even see them in a microscope. So how can we measure their size? Atoms and molecules act as little cavities that can be probed with light waves. The resonant frequencies of the atoms and molecules can be measured. To turn these measurements into dimensions of the cavity we need a theory to go along with the measurement. This theory is called quantum mechanics.

2) We can measure things that are far away. For example, we can learn about astronomical objects, such as starts, galaxies, binary starts, the big bang, by measuring the frequencies emitted by these objects. Indeed, we can weigh distant stars and actually determine the dimensions of the universe with similar techniques!

3) We can measure things that we donít want to get near Ė spying is an excellent example! During the Cold War the Soviet government presented a fancy plaque to the American Embassy in Moscow. The Americans were, of course, extremely suspicious of this gift, so the examined the plaque, took x-rays of it, etc., but could not find anything wrong with it. So, they hung the plaque up in the embassy. A few weeks later, the Americans noticed that the Russians were beaming microwave radiation at the embassy, but they could not figure out why. Finally, a scientist put it all together. The microwaves were probing a cavity in the plaque. The cavity had a flexible membrane over it. As people talked in the embassy, the membrane would vibrate, changing (very slightly) the dimensions of the cavity. The microwaves could measure the dimensions of the cavity, and thus, reconstruct the change in the size of the cavity. In the end, the cavity became a microphone that could be monitored from far away, allowing the Russians to eavesdrop on the embassy!

4) We can measure things that are delicate. When fitting hearing aids, it is very important to know the length of the ear canal because if the hearing aid is too long it will puncture the eardrum. So, how do audiologists measure the length of the ear canal? They do not want to stick a ruler in the ear, as, again, the eardrum could be damaged. However, the ear canal is essentially a closed-open air column. By measuring its resonant frequencies, its length can be determined. This is actually how the ear canal is measured for fitting hearing aids.

5) We can measure things that are dangerous. As mentioned above, if we have an acoustic cavity, we can learn something about the contents of the cavity. After the Gulf War, we wanted to find all of the chemical weapons that might be in Iraq. So, soldiers would go into a bunker and find artillery shells. However, they were not marked as being conventional or chemical weapons. How did the soldiers determine the contents? Obviously, they would not want to open or detonate the shells, as the poison would be released if it were a chemical weapon. So, they did an experiment identical to the one we did in Lab4. They attached to piezoelectric transducers to the artillery shell. Piezoelectric transducers are simple devices that act as speakers and microphones but work at much higher frequencies than we used in the lab. They would then scan the frequency going into the speaker from 1 to 1000 kHz and measure the output of the microphone. By analyzing all of the resonant frequencies, they could determine what was inside!

6) We can measure things inside of us. Medical imaging is a very important application of these techniques. While a fetus is growing, it is good to be able to measure its size to determine if it is growing properly. However, it is not an option to put a ruler up to it, in order to measure it! Here again, an arrangement of ultrasonic speakers and microphones can produce an image of the fetus or many other objects in the body. This is generally known as an ultrasound image.

It is actually quite amazing how one relatively simple technique can have so many important and even lifesaving applications.

Music of the Spheres - Revisited

Before concluding this chapter, we need to return to where we started Ė Pythagoras and the Music of the Spheres. We have shown how Pythagorasís simple question, "Were does the musical scale come from?" set off a chain of events which led ultimately to the development of modern science and fantastic technological applications. However, we also saw how Pythagorasís work led to the concept of the Music of the Spheres, which held back the field of astronomy for a long time. So, the question is: why didnít the Music of the Spheres work for the astronomers?

Pythagoras studied music, and music is based on waves, sound waves, in particular. However, planets are objects and large objects simple are not described by waves. There was no reason for planets to have any connection to music.

Now all of this changed in the early 1900ís with the development of Quantum Mechanics. The physicists who invented Quantum Mechanics speculated that objects actually ARE waves, although they realized that the large the object, the harder it would be to see that it is a wave. Even today, we cannot see that anything larger than a molecule is actually a wave.

However, electrons are very small and do act as waves. It was originally thought the electrons are small objects that orbit around a positively charged nucleus just like the planets move around the sun. As it turned out, many properties of atoms and molecules could not be explained with this model.

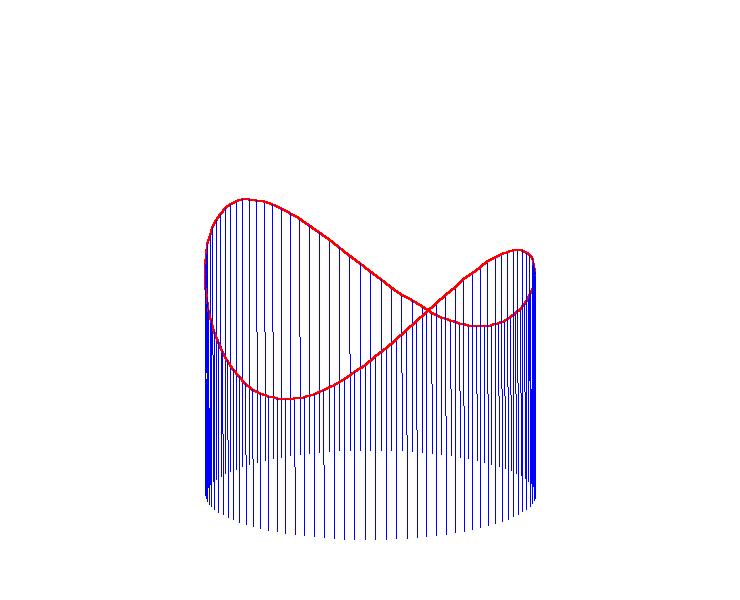

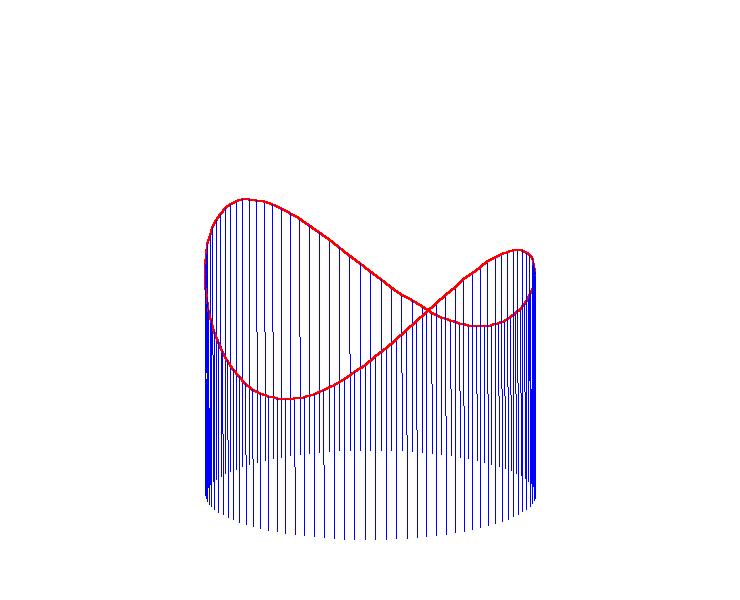

When it was realized that electrons are actually waves, physicists changed the model and postulated that the electron wave only has certain modes of vibration, just like the modes of a string or an air column. The modes look a little different than the modes of a string, because the electron still wraps around the nucleus, but the idea is the same. The modes would look something like this:

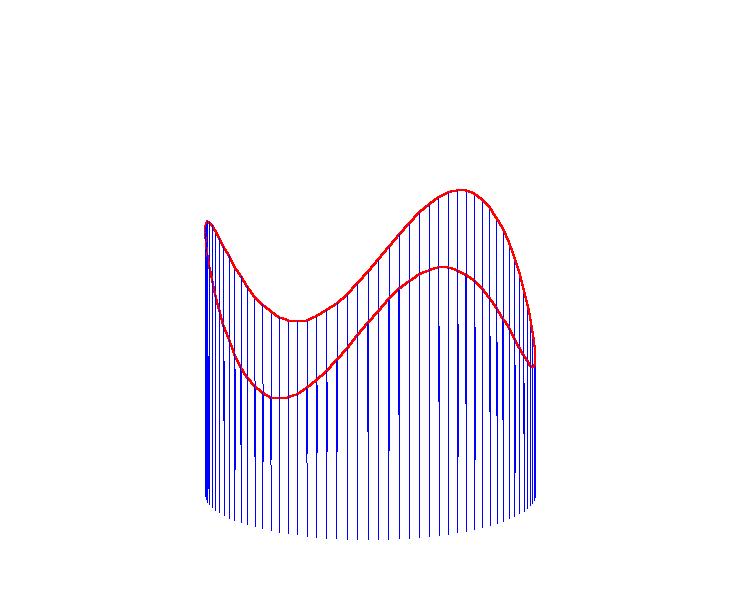

Or this:

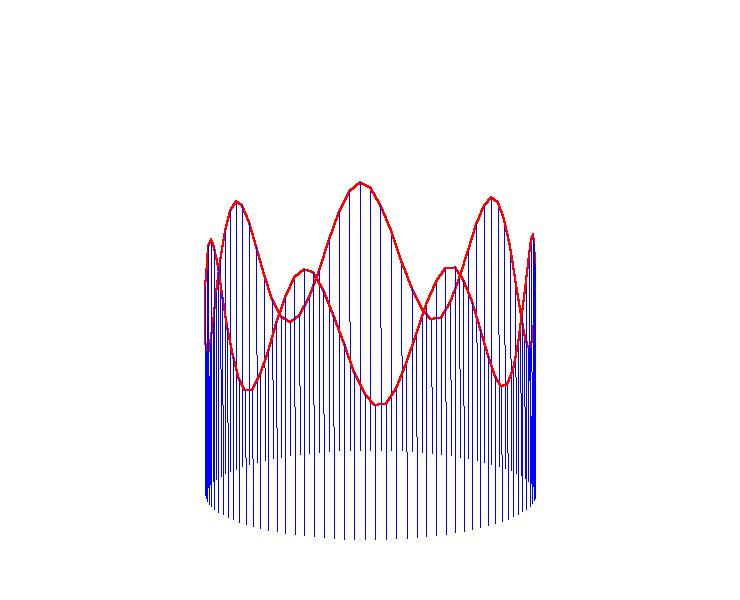

Or even:

Now, only certain modes are possible and are determined by fitting in an integer number of cycles around the nucleus. This is called "quantization" Ė the fact that only integer numbers of wavelengths are possible Ė leading to the theory of "Quantum Mechanics". Because of this, the possible modes of the electron are related to small integers, just like the musical scale. So, in the end, the motion of an electron in an atom forms an order much like the order of the Music of the Spheres!

In fact, many of the founders of quantum mechanics studied and were influenced by musical acoustics and the problem of consonance and dissonance and this probably helped them to finally understand the true structure of electrons in atoms.